How To Use Common Songwriting Chord Progressions To Write Better Music

Are you looking for chords that you can use to write music? If you are like a lot of musicians, you sometimes struggle to think of good chord progressions for songwriting. That said, if you are having a hard time thinking of chords to use in your songs, it’s likely that you are experiencing one of the following problems:

- You don’t know how to put chords together one after the other in a progression that sounds good.

- You are familiar with common chord progressions used by other musicians (and use them in music). However, you don’t have a fundamental understanding of WHY these chords seem to work so well together, and are unable to use them in a highly creative manner.

In order to improve your ability to create great songwriting chord progressions, it is important to understand how chords work together from a fundamental standpoint. Once you understand what makes certain chord choices more effective than others in any given situation, you will be able to write much better and more expressive songs.

To help you get started writing better songs with the chords you choose, I am going to use the rest of this article to explain the general idea for how common chord progressions work. Keep in mind that “common chord progressions” do not necessarily mean “chords that sound like what everyone else is doing.” Rather, they are chords that have been proven to ‘sound good’ due to the way they are arranged together naturally. No matter what chords you choose in your songwriting, there are MANY different musical tools that you can use to make them sound unique.

Organizing Your Songwriting Chord Progressions With Roman Numerals

One of the most important ideas to understand when coming up with chord progressions for songwriting is the concept of roman numerals. If you have ever tried to find information about using chords to write music, you likely know of roman numerals already. For example, you may have heard someone say “A major is the “V” (five) chord in the key of D major.” or “That progression that you are playing is a I – IV – V (pronounced: one – four – five). These numbers being used to refer to chords are roman numerals. Roman numerals are a very useful tool for helping songwriters organize the chords they use in music.

Ok, so what exactly are roman numerals? They are numerals that number the chords of any given major or minor scale starting from 1 (the first note of the scale) and going to 7 (the last note of the scale).

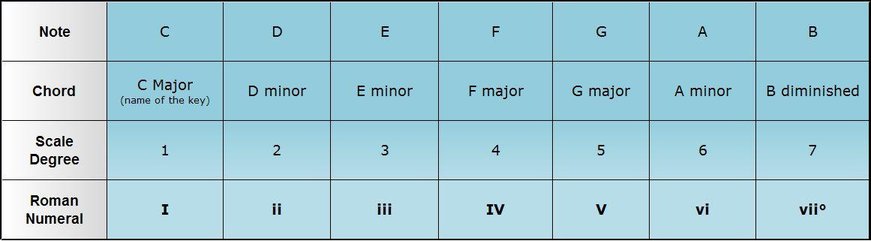

Roman numerals are written as follows:

Major chords are represented by upper case letters - (Example: I, IV, V)

Minor chords are represented by lower case letters - (Example: vi, ii, iii)

Diminished chords will be lower case with a “°” sign next to them - (Example: vii°, ii°)

Augmented triads will be upper case with a “+” sign next to them - (Example: III+, V+)

Here is a chart to show you what this looks like in the key of C major:

How Common Chord Progressions Are Made And Why They Work

First, before I show you how to make chord progressions for your songwriting, it is necessary to briefly discuss what is going on when we use different chords to write songs:

Starting from a fundamental level, when you play two pitches either at the same time or one after the other, they will ‘feel’ a certain way based off of which pitches you choose. This is because our brains naturally process both notes in relation to one another. For example, if you play the note “A” followed by the note “B”, it will feel different than if you play an “A” note followed by the note “C#.” Although there is much more detailed and interesting science behind why this is; I will not be discussing it in this article. The main point to understand here is that the way a note ‘feels’ will vary depending on how far away it is from another note (in terms of pitch).

That said, this concept applies not only to individual notes, but to groups of notes as well (chords). For example, notice how different these common chord progressions feel by simply changing only one chord:

A major – D major – E major

A major – D major – F# minor

It may seem obvious to point out that these chord progressions with different chords feel different from one another; however, it is this fundamental understanding that has caused musicians over many centuries to experiment with endless combinations of chords in order to identify patterns for how each one “leads” to another. As a result, songwriters have developed a system of general guidelines that allow them to be able to use chord progressions to lead the listener in a specific direction.

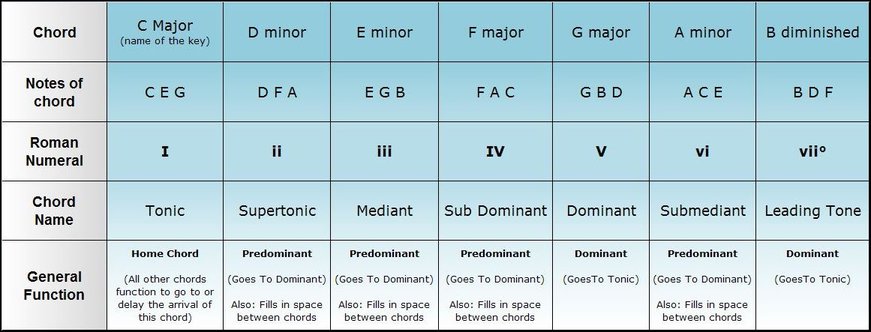

To make it easier to identify how a chords work when used together, names are given to each chord in a key. To show you how this works, I have created a chart that shows you the chord name and general function of a chord in a major key. Observe the chart below:

As you can see above, each chord has a specific function. By using this chart, you can start to get a feel for using chord progressions in songwriting to create a sense of direction in your music.

*Note*:

- There more “functions” than what is written in the chart above. This chart is only intended to help you get started writing chord progressions.

- This chart applies to all major keys (not just C major), and also applies similarly (but not exactly the same) to minor keys.

Example Chord Progressions For Songwriting And Tips For Creating Your Own

Using the chart from above, here are some examples that use common chord progressions to help you understand how this works:

Example 1: C major (I) – F major (IV) – G major (V) – C major (I)

Generally referred to as a “I – IV – V” progression, this is one of the most common chord progressions in music, and it creates a very strong sense of direction. Why is this? As I explained above, different notes “pull” toward each other depending on how far away they are in pitch. In this case, the I – IV has a very strong pull, and so does the V – I. This is because the lowest note (root) in each of these chords is either a “5th” or a “4th” apart from the next. For the purposes of this article, this simply means that the notes are either 4 or 5 note letters away.

You can determine this by looking at the chart above

- In this case, the first two chords are “C major” and “F major”.

- The lowest notes in these chords are “C” and “F”.

- In the C major scale (C D E F G A B), “F” is 4 letters above “C”, and 5 letters below “C” counting “C” as the first letter.

If you want to create chord progressions in your songwriting that give a strong sense of direction to the music, using chords that have roots a 5th/4th apart is your best choice. Alternatively, a weaker choice would be roots by 3rd/6th, and finally the weakest choice: roots by 2nd/7th. To observe how this feels, compare the following progressions where example 2 uses mostly chords that move by 4th/5th and example 3 uses only chords that move by 2nd/7th:

Example 2: C major (I) – F major (IV) – D minor (ii) – G major (V) –C major (I)

Example 3: C major (I) – D minor (ii) - E minor (iii) - D minor (ii) – C major (I)

With these two examples, you can notice how strong the pull is one from chord to the next even more by playing only the root note from each chord. As you choose chord progressions for songwriting, keep this idea of “strong versus weak” in mind. A strong chord progression can help you create feelings of direction, certainty, and closure. On the other hand, you can use weaker chord progressions to achieve the opposite effect. Using a balance of both will help keep your music interesting throughout the entire song.

To further explain this, I am going to use “chord names” from the chart above:

In music, the chords of a key are naturally set up to move from the Tonic chord (I) to a chord with a dominant function (V or vii°) with predominant chords in between. This is what makes your music have a sense of direction. In general (for major keys), this progression has the effect of uplifting those who hear it. However, the opposite can be achieved by using what is called “retrogression.” This means instead of progressing from the Tonic to Dominant, your chords go “backwards” from the Dominant to Subdominant (or any other chord with a predominant function). This is a very powerful way to create negative or sad feelings in your music. Here are some examples:

Chord Progressions:

- [Key: C major] C major (I) –D minor (ii) – G major (V) – C major (I)

- [Key: G major] G major (I) – A minor (ii) – C major (IV) – D major (V)

Chord Retrogressions:

- [Key: C major] C major (I) –G major (V) – F major (IV) – A minor (ii) – G major (V)

- [Key: A major] A major (I) – E major (V) – F# minor (vi) – D major (IV) - F# minor (vi) – E major (V) – A major (I)

After reading through the ideas of this article, you should now have a good idea of how chords are used together with one another to create direction in music. By simply considering these ideas as you choose chords, you can figure out nearly endless combinations of chord progressions for songwriting that will achieve a different ‘feel’ in your music. Each time you use a new chord progression, write down the roman numerals or chord names (Tonic, Dominant, etc.) and keep track of how each one feels. By doing this, you will quickly learn how to control the way your music feels with your chord choices. Additionally, there are even more variables to consider by adding in the other musical elements such as melody, rhythm or song structure!

Now that you understand how common chord progressions work, you are ready to learn about 5 incredibly powerful (and lesser-known) chord progressions that will enhance your music and make it stand out from the rest. Take your songs to the next level by downloading right now your free eBook on chord progressions for songwriters (click on the button below):

Become a better guitar player with personalized electric guitar lessons .